Fairy tales are good to think with.

Compact yet also capacious, with

roots in myth, they were engineered

to accommodate changes in cultural

values and conflicts. “Snow White”

is no exception. Rupert Sanders’s

film “Snow White and the

Huntsman” the latest version of the

tale, takes us into a wilderness of

environmental depredations and

dynastic conflict. Charlize Theron’s

fair-haired wicked queen presides

over subjects with ravaged faces in

landscapes that resemble toxic oil

spills; in her shape-shifting magic,

she reconstitutes herself at one point

from what looks like a flock of crows

caught in an oil slick. Her rule has

no doubt created the viscous black

horrors that Snow White encounters

in the denuded woods to which she

flees. The film’s raven-haired

heroine, by contrast, soothes savage

beasts with her compassionate face

and, as a digitally miniaturized Bob

Hoskins, playing one of the seven

dwarfs, proclaims: “she will heal the

land.” But she’s no passive, guiltless

damsel. Her exquisite beauty,

combined with charismatic

leadership, enables her to defeat the

evil queen and redeem the desolate

landscape of the kingdom.

This Snow White is very different

from the one we find in the

canonical literary version recorded

in the early nineteenth century. The

Brothers Grimm called their story

“Little Snow White,” to emphasize

the innocence and vulnerability of a

young girl persecuted by her jealous

stepmother. Their heroine is

precociously stunning—“When she

was seven years old she was as

beautiful as the light of day, even

more beautiful than the queen

herself”—and her beauty inspires

huntsman, dwarfs, and prince alike

to protect her from a less fair,

wicked queen. The early tale is also

a reflection on children’s fears

about the cruelty of stepmothers, at

a time when mortality rates for

child-bearing women were

exceptionally high. The concept of

the “blended” family was foreign to

the Grimms’ era, and it remains so

in new inflections of the tale. Snow

White delivers a timely message

about survival even when the odds

are not in your favor, as they surely

are not for the heroine of “Snow

White and the Huntsman,” who

must now stand up to both a

perverse stepmother and a hostile

Mother Nature.

A 1912 Broadway musical first gave

the story the title by which we know

it today: “Snow White and the Seven

Dwarfs.” The miniature miners of

the Grimms’ tale now had whimsical

names and personalities—an

antidote to the tale’s dark themes.

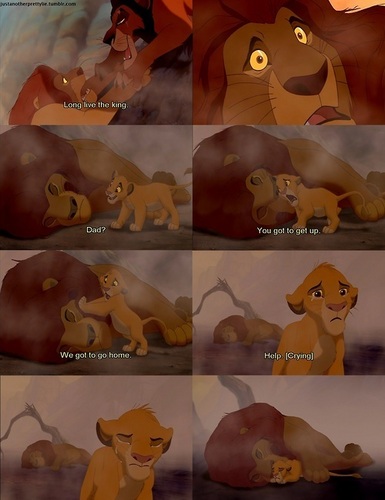

The Disney version (from 1937), too,

draws much of its charm from the

allegorical vigor of Doc, Grumpy,

Happy, Sleepy, Bashful, Sneezy and

Dopey, and, in addition, gives Snow

White a new mission. The Grimms’

girl was something of an intruder, a

Goldilocks figure who discovers an

enviably “neat and clean” cottage,

along with seven little beds—one

“just right”—covered with white

sheets. Disney’s heroine, by contrast,

is given a Depression-era work ethic

and cleans up a house that appears

to be occupied by what she

disapprovingly refers to as “seven

untidy little children.” Whistling

while she works, she is a kindred

spirit to the dwarfs, who descend

into the mines to carry out their

subterranean work “from early

morn ’til night,” yet cheerfully

intone: “we don’t know / what we

dig ’em for.” Something of a “dumb

bunny,” as the Anne Sexton calls her

in a poem from “Transformations,”

Snow White falls victim three times

to the camouflaged wicked queen.

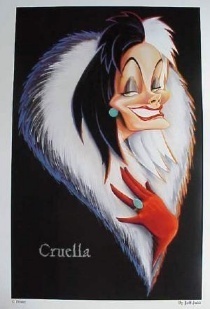

Grimm purists regard the Disney

version as a sentimental confection,

but Disney animators preserved the

fairy tale’s powerful engagement

with a child’s fears about parental

persecution and abandonment,

while also capturing adult anxieties

about aging and loss. After drinking

the magic cocktail she has brewed,

the queen’s hair turns white, her

hands become gnarled with age

(“Look, my hands!”), her voice turns

into a throaty cackle (“My voice!”),

and finally she emerges from under

her dark cloak as a hunchbacked

crone. The horror of the queen’s

transformation from a beautiful

woman into an abject old hag is still

potent.

Anne Sexton may well have had

Disney’s transformation scene in

mind when her wicked queen

condemns Snow White to be

“hacked” to death after she herself

discovers “brown spots on her hand”

and “four whiskers over her lip.”

Sexton’s emphasis on the stepmother

prefigured the nineteen-seventies

protests against the Disneyfication of

fairy tales, with Sandra Gilbert and

Susan Gubar leading the charge in

their preface to “The Madwoman in

the Attic,” a landmark work of

feminist criticism. They proposed

calling the story “Snow White and

Her Wicked Stepmother,” arguing

that the queen—inventive, active,

and mobile—was far more

enthralling than her insipid

stepdaughter.

With “Snow White and the

Huntsman,” the tale has been

reconceived to appeal to an

audience partial to high-decibel

special effects, monsters and

vampires, triangulated teen

romance, epic battle scenes, and

young warrior women who, like

Katniss Everdeen in “The Hunger

Games” or Merida in Pixar’s

“Brave,” have appropriated not only

the wicked queen’s inventive energy

but also the huntsman’s proficiency

with weapons. The film preserves

the central motifs of the Snow White

plot: mother-daughter rivalry, magic

mirror, compassionate huntsman,

seven dwarfs, poisoned apple, and

redemptive kiss—with all but the last

steroid-enhanced through high-tech

cinematic magic. Like all fairy-tale

adaptations, it also operates like a

magnet, picking up relevant bits and

pieces of the culture that is recycling

the tale.

Kristen Stewart’s Snow White is

nothing like the charmingly goofy

princess of Disney’s live-action

“Enchanted” or the spunky yet

vulnerable Snow White in ABC’s

series “Once Upon a Time.” More

like a serious cousin to the spirited

and radiantly youthful Snow White

of Tarsem Singh’s campy recent

film, “Mirror Mirror,” she is ready

for action. This Snow White becomes

a “pure and innocent” warrior

princess, an angelic savior who

channels Joan of Arc and Tolkien’s

Aragorn, as well as the four Pevensie

siblings from C. S. Lewis’s “The

Chronicles of Narnia,” to save the

kingdom of her late father (stabbed

to death by the queen on their

wedding night). Everyone is armed,

and swords, scimitars, axes, snares,

and shields feature as prominently

in this film as they do in the Middle

Earth of “The Hobbit.” Romance is

edged out by the racing energy of

horses speeding through dramatic

landscapes and by expertly

choreographed combat scenes. This

is a Snow White designed to appeal

to viewers of all ages, and to men

and women alike.

“Snow White and the Huntsman”

captures deepening anxiety about

aging and generational sexual

rivalry in clever, self-reflexive ways,

with Charlize Theron as a beautiful

cougar (and established Hollywood

star) threatened by a younger, sylph-

like Kristin Stewart. In the world of

the film, beauty is the locus of

female power, and is thereby

fleeting in its effects (men are

“enchanted” by women but “use”

them until they eventually “tire” of

them); it is the source of both

fascination and horror. Early on, we

learn the wicked queen’s backstory:

she was abandoned by her first

husband for a younger woman. This

is meant to explain why she is so

desperate to suck the life force out of

local virgins, to dine on the vital

organs of birds, and to reap the

cosmetic effects of baths in

mysterious white fluids.

The queen’s quest for lasting youth

is part of the story’s larger

exploration (in the tradition of

many great myths) of how humans

relate to the natural world—whether

we are of it or have mastered and

moved beyond it. Efforts to remain

forever young violate the natural

order of generational succession and

imperil life itself. The woods have

always been terrifying, but never

more so than in this new version of

the tale, in which a despoiled Mother

Nature mirrors and magnifies the

wicked queen’s frenzied assaults on

humans. “Snow White and the

Huntsman” holds a mirror up to our

own vanity, narcissism, and

recklessness, emphatically

reminding us, as Charlize Theron

proclaims shortly before her

downfall, that every world gets the

wicked queen it deserves.

Compact yet also capacious, with

roots in myth, they were engineered

to accommodate changes in cultural

values and conflicts. “Snow White”

is no exception. Rupert Sanders’s

film “Snow White and the

Huntsman” the latest version of the

tale, takes us into a wilderness of

environmental depredations and

dynastic conflict. Charlize Theron’s

fair-haired wicked queen presides

over subjects with ravaged faces in

landscapes that resemble toxic oil

spills; in her shape-shifting magic,

she reconstitutes herself at one point

from what looks like a flock of crows

caught in an oil slick. Her rule has

no doubt created the viscous black

horrors that Snow White encounters

in the denuded woods to which she

flees. The film’s raven-haired

heroine, by contrast, soothes savage

beasts with her compassionate face

and, as a digitally miniaturized Bob

Hoskins, playing one of the seven

dwarfs, proclaims: “she will heal the

land.” But she’s no passive, guiltless

damsel. Her exquisite beauty,

combined with charismatic

leadership, enables her to defeat the

evil queen and redeem the desolate

landscape of the kingdom.

This Snow White is very different

from the one we find in the

canonical literary version recorded

in the early nineteenth century. The

Brothers Grimm called their story

“Little Snow White,” to emphasize

the innocence and vulnerability of a

young girl persecuted by her jealous

stepmother. Their heroine is

precociously stunning—“When she

was seven years old she was as

beautiful as the light of day, even

more beautiful than the queen

herself”—and her beauty inspires

huntsman, dwarfs, and prince alike

to protect her from a less fair,

wicked queen. The early tale is also

a reflection on children’s fears

about the cruelty of stepmothers, at

a time when mortality rates for

child-bearing women were

exceptionally high. The concept of

the “blended” family was foreign to

the Grimms’ era, and it remains so

in new inflections of the tale. Snow

White delivers a timely message

about survival even when the odds

are not in your favor, as they surely

are not for the heroine of “Snow

White and the Huntsman,” who

must now stand up to both a

perverse stepmother and a hostile

Mother Nature.

A 1912 Broadway musical first gave

the story the title by which we know

it today: “Snow White and the Seven

Dwarfs.” The miniature miners of

the Grimms’ tale now had whimsical

names and personalities—an

antidote to the tale’s dark themes.

The Disney version (from 1937), too,

draws much of its charm from the

allegorical vigor of Doc, Grumpy,

Happy, Sleepy, Bashful, Sneezy and

Dopey, and, in addition, gives Snow

White a new mission. The Grimms’

girl was something of an intruder, a

Goldilocks figure who discovers an

enviably “neat and clean” cottage,

along with seven little beds—one

“just right”—covered with white

sheets. Disney’s heroine, by contrast,

is given a Depression-era work ethic

and cleans up a house that appears

to be occupied by what she

disapprovingly refers to as “seven

untidy little children.” Whistling

while she works, she is a kindred

spirit to the dwarfs, who descend

into the mines to carry out their

subterranean work “from early

morn ’til night,” yet cheerfully

intone: “we don’t know / what we

dig ’em for.” Something of a “dumb

bunny,” as the Anne Sexton calls her

in a poem from “Transformations,”

Snow White falls victim three times

to the camouflaged wicked queen.

Grimm purists regard the Disney

version as a sentimental confection,

but Disney animators preserved the

fairy tale’s powerful engagement

with a child’s fears about parental

persecution and abandonment,

while also capturing adult anxieties

about aging and loss. After drinking

the magic cocktail she has brewed,

the queen’s hair turns white, her

hands become gnarled with age

(“Look, my hands!”), her voice turns

into a throaty cackle (“My voice!”),

and finally she emerges from under

her dark cloak as a hunchbacked

crone. The horror of the queen’s

transformation from a beautiful

woman into an abject old hag is still

potent.

Anne Sexton may well have had

Disney’s transformation scene in

mind when her wicked queen

condemns Snow White to be

“hacked” to death after she herself

discovers “brown spots on her hand”

and “four whiskers over her lip.”

Sexton’s emphasis on the stepmother

prefigured the nineteen-seventies

protests against the Disneyfication of

fairy tales, with Sandra Gilbert and

Susan Gubar leading the charge in

their preface to “The Madwoman in

the Attic,” a landmark work of

feminist criticism. They proposed

calling the story “Snow White and

Her Wicked Stepmother,” arguing

that the queen—inventive, active,

and mobile—was far more

enthralling than her insipid

stepdaughter.

With “Snow White and the

Huntsman,” the tale has been

reconceived to appeal to an

audience partial to high-decibel

special effects, monsters and

vampires, triangulated teen

romance, epic battle scenes, and

young warrior women who, like

Katniss Everdeen in “The Hunger

Games” or Merida in Pixar’s

“Brave,” have appropriated not only

the wicked queen’s inventive energy

but also the huntsman’s proficiency

with weapons. The film preserves

the central motifs of the Snow White

plot: mother-daughter rivalry, magic

mirror, compassionate huntsman,

seven dwarfs, poisoned apple, and

redemptive kiss—with all but the last

steroid-enhanced through high-tech

cinematic magic. Like all fairy-tale

adaptations, it also operates like a

magnet, picking up relevant bits and

pieces of the culture that is recycling

the tale.

Kristen Stewart’s Snow White is

nothing like the charmingly goofy

princess of Disney’s live-action

“Enchanted” or the spunky yet

vulnerable Snow White in ABC’s

series “Once Upon a Time.” More

like a serious cousin to the spirited

and radiantly youthful Snow White

of Tarsem Singh’s campy recent

film, “Mirror Mirror,” she is ready

for action. This Snow White becomes

a “pure and innocent” warrior

princess, an angelic savior who

channels Joan of Arc and Tolkien’s

Aragorn, as well as the four Pevensie

siblings from C. S. Lewis’s “The

Chronicles of Narnia,” to save the

kingdom of her late father (stabbed

to death by the queen on their

wedding night). Everyone is armed,

and swords, scimitars, axes, snares,

and shields feature as prominently

in this film as they do in the Middle

Earth of “The Hobbit.” Romance is

edged out by the racing energy of

horses speeding through dramatic

landscapes and by expertly

choreographed combat scenes. This

is a Snow White designed to appeal

to viewers of all ages, and to men

and women alike.

“Snow White and the Huntsman”

captures deepening anxiety about

aging and generational sexual

rivalry in clever, self-reflexive ways,

with Charlize Theron as a beautiful

cougar (and established Hollywood

star) threatened by a younger, sylph-

like Kristin Stewart. In the world of

the film, beauty is the locus of

female power, and is thereby

fleeting in its effects (men are

“enchanted” by women but “use”

them until they eventually “tire” of

them); it is the source of both

fascination and horror. Early on, we

learn the wicked queen’s backstory:

she was abandoned by her first

husband for a younger woman. This

is meant to explain why she is so

desperate to suck the life force out of

local virgins, to dine on the vital

organs of birds, and to reap the

cosmetic effects of baths in

mysterious white fluids.

The queen’s quest for lasting youth

is part of the story’s larger

exploration (in the tradition of

many great myths) of how humans

relate to the natural world—whether

we are of it or have mastered and

moved beyond it. Efforts to remain

forever young violate the natural

order of generational succession and

imperil life itself. The woods have

always been terrifying, but never

more so than in this new version of

the tale, in which a despoiled Mother

Nature mirrors and magnifies the

wicked queen’s frenzied assaults on

humans. “Snow White and the

Huntsman” holds a mirror up to our

own vanity, narcissism, and

recklessness, emphatically

reminding us, as Charlize Theron

proclaims shortly before her

downfall, that every world gets the

wicked queen it deserves.