LANGUAGE SKILL ATTRITION AND MAINTENANCE

Just as human beings possess a great capacity to acquire language, they also have a capacity for losing it. Although some individuals have experienced language loss or attrition as a result of a head wound, stroke, or other source of brain damage, many more have lost language skills through lack of a linguistically appropriate social environment in which to use them. Instances include: a speaker of a language who lives in an environment in which another language is considered more socially useful; a speaker of a language who moves to a country where a different language is spoken and, as a result, gradually loses his or her first language; and a student who has learned a second language in school and loses it through lack of opportunity to practice the skills acquired. Differences in proficiency among second language speakers may be obvious; some are able to maintain their skills, while others forget most or all of what they once knew. Millions of individuals who have studied a second language in high school or college for several years have lost the ability to hold the most basic conversation. Millions who as children or young people were monolingual speakers of other languages are now monolingual speakers of English, no longer able to speak their mother tongue.

Language acquisition and maintenance depend on instructional factors, relating to the way in which the language is initially acquired; cultural factors, relating to the status and usefulness of the language in a particular society; and personality factors, relating to individual characteristics of the speaker.

INSTRUCTIONAL FACTORS

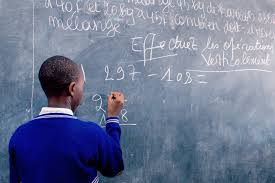

Curriculum and instructional methods in language teaching may be very different if the goal is to foster language skills and language-learning skills that can be maintained after formal instruction ends, rather than merely to produce a given level of competence by semester's end. Research in second language acquisition and attrition suggests the following factors in maintaining language skills.

"Instructional Objectives." Studies of attrition of foreign language skills acquired in the classroom suggest that receptive skills may be less vulnerable to attrition than productive skills. For example, studies have reported little diminishment, during a summer vacation period, in students' understanding of grammatical concepts and vocabulary . In contrast, language production by kindergarten immersion students over a similar period of interrupted exposure showed a decrease in utterance length and an increase in overall error rate .

The differential attrition rate between receptive and productive skills is supported by the various rates of acquisition observed in many individuals. Young children acquiring their first language display rather sophisticated comprehension skills, including understanding of grammatical rules, while their productive skills may be rudimentary at best. Nearly all adult speakers have some measure of receptive control over more than one dialect of their native language; for example, comprehending a British dialect presents little difficulty for most American English speakers, yet few are able to speak or reproduce the dialect convincingly.

Students whose instruction has focused primarily on oral skills may show more rapid and extensive attrition than those whose course of study stressed comprehension and writing skills. Unlike spoken language, the written medium allows the reader to decode at his or her own speed and to reexamine parts that may be unclear on a single reading. Indeed, most learners will not experience attrition equally across all skill areas.

"Intensity of Instruction." While length of time spent studying a language is related to ultimate achievement, the distribution of study over time is also important. Results of the Ottawa-Carleton French Project, for example, indicated that students enrolled for one year in a program, where half of each day's classes were conducted in French, made more progress than students exposed to the same number of hours' instruction spread over two years .Intensive programs of instruction have been reported to yield better results than less intensive programs of the same number of hours of instruction .These studies suggest that individuals intensively exposed to a language may use language acquisition processes different from those used by individuals involved in learning a language in chunks over long periods of time. Subsequent attrition rates may also differ for students of intensive and nonintensive programs of instruction.

"Developmental Considerations." Language learners of different ages and developmental levels bring different strengths and natural abilities to the language learning task. Children, for example, have a remarkable facility for rote memorization, and often retain intact memories in adulthood of material that has been untapped for years or decades. Adults, on the other hand, have metalinguistic and metacognitive skills superior to those of children. Their more advanced cognitive level allows them to rely on language consciously, to organize material in ways that will facilitate acquisition, and to recognize and plan for the possibility that skills may slowly deteriorate. The degree to which instructional methods capitalize on these developmental differences not only influences the learner's ease and success in acquisition, but may also affect the extent to which attrition is avoided.

"Curriculum Design." Foreign language instructors may incorporate maintenance techniques into the acquisition process by modifying the conventional linear syllabus to allow for the recycling of vocabulary and grammatical structures. Such design would permit review within the acquisition process, rather than requiring learners to refurbish their skills by plodding through the original material in exactly the same form as before. Research on specific design features that may prevent or slow down attrition is in its preliminary stages.

CULTURAL FACTORS

How do public attitudes toward bilingualism and the relative prestige of different languages influence the maintenance of second language skills? Insight may be gained from situations in which two or more languages come into contact. Such contact may occur for many different reasons, including, for example, changes in political boundaries, industrialization, emigration, and intermarriage. The result of language contact is usually a gradual shift in use from one language to the other. Factors related to language attrition or even the death of a language or dialect include the number and geographic concentration of speakers, age distribution of speakers, immigration patterns, and speaker literacy in the language involved. In instances in which one language is considered more prestigious than the other, it is unlikely that the less prestigious language would thrive across several generations. Chances of survival are even further reduced when negative attitudes toward bilingualism and strong societal pressures to assimilate are prevalent. Language shift from minority languages to English is particularly rapid in the United States, where the pressure for immigrant groups to assimilate linguistically has become so overt that several states have passed measures making English their "official state language." This kind of environment discourages bilingualism and hinders the study and maintenance of skills in languages other than English. In much the same way that a language restricted in domains of use becomes an impoverished and threatened language, an individual learner's language skills are prone to attrition in domains in which they are rarely used. For this reason, the presence of a strong ethnic community is important for the maintenance of foreign language skills. Foreign language learners can avail themselves of linguistic resources such as films, lectures, and newspapers in the foreign language. Large ethnic communities may also produce minority-language television broadcasts and sponsor live cultural events. These types of activities and resources provide valuable opportunities for foreign language learners to maintain their language skills.

PERSONAL FACTORS

A number of personality factors have been correlated positively with success in learning foreign languages. These include the willingness to take certain kinds of risks, good pattern recognition skills, tolerance for ambiguity in a number of situations, and an outgoing and social nature. A study found that non-English-speaking children who acquired English easily in an American school were those who sought out and became friendly with native speakers of English, taking advantage of every opportunity to socialize with these children and to practice their English skills . Moreover, learners of a foreign language are more successful if they understand the need to learn the language, and if they are motivated to do so . Indeed, the more positively the learner feels toward the language, the speakers, and the culture associated with the language being learned, the greater the progress that is made. There is a large body of research on the relationship among attitude, motivation, and language learning .The age of the learner acquiring the foreign language does make a difference because the chances of acquiring native-like speech appear to decrease over time. However, older students appear to learn morphology and syntax more quickly than young children. Students of all ages have an excellent chance of becoming proficient second language speakers if they are well-motivated, find the language interesting, and believe that the language is spoken by the kind of people they themselves would like to emulate.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE

Attrition is a powerful force, potentially causing even the most diligent and motivated learner or speaker to lose language skills that took years to acquire. Language study that helps the student to use the personal and cognitive strategies used by "expert learners" will enhance the likelihood of language skill maintenance; courses of study in which positive cultural attitudes are fostered and in which maintenance techniques are incorporated can help prevent attrition. Beyond these techniques, individuals can prevent attrition of their skills through travel abroad, the use of computer-aided instruction, self-instruction, and specific uses of cultural resources in their local ethnic communities. These techniques are described at length in You CAN Take It With You: Helping Students Maintain Foreign Language Skills Beyond the Classroom.

Just as human beings possess a great capacity to acquire language, they also have a capacity for losing it. Although some individuals have experienced language loss or attrition as a result of a head wound, stroke, or other source of brain damage, many more have lost language skills through lack of a linguistically appropriate social environment in which to use them. Instances include: a speaker of a language who lives in an environment in which another language is considered more socially useful; a speaker of a language who moves to a country where a different language is spoken and, as a result, gradually loses his or her first language; and a student who has learned a second language in school and loses it through lack of opportunity to practice the skills acquired. Differences in proficiency among second language speakers may be obvious; some are able to maintain their skills, while others forget most or all of what they once knew. Millions of individuals who have studied a second language in high school or college for several years have lost the ability to hold the most basic conversation. Millions who as children or young people were monolingual speakers of other languages are now monolingual speakers of English, no longer able to speak their mother tongue.

Language acquisition and maintenance depend on instructional factors, relating to the way in which the language is initially acquired; cultural factors, relating to the status and usefulness of the language in a particular society; and personality factors, relating to individual characteristics of the speaker.

INSTRUCTIONAL FACTORS

Curriculum and instructional methods in language teaching may be very different if the goal is to foster language skills and language-learning skills that can be maintained after formal instruction ends, rather than merely to produce a given level of competence by semester's end. Research in second language acquisition and attrition suggests the following factors in maintaining language skills.

"Instructional Objectives." Studies of attrition of foreign language skills acquired in the classroom suggest that receptive skills may be less vulnerable to attrition than productive skills. For example, studies have reported little diminishment, during a summer vacation period, in students' understanding of grammatical concepts and vocabulary . In contrast, language production by kindergarten immersion students over a similar period of interrupted exposure showed a decrease in utterance length and an increase in overall error rate .

The differential attrition rate between receptive and productive skills is supported by the various rates of acquisition observed in many individuals. Young children acquiring their first language display rather sophisticated comprehension skills, including understanding of grammatical rules, while their productive skills may be rudimentary at best. Nearly all adult speakers have some measure of receptive control over more than one dialect of their native language; for example, comprehending a British dialect presents little difficulty for most American English speakers, yet few are able to speak or reproduce the dialect convincingly.

Students whose instruction has focused primarily on oral skills may show more rapid and extensive attrition than those whose course of study stressed comprehension and writing skills. Unlike spoken language, the written medium allows the reader to decode at his or her own speed and to reexamine parts that may be unclear on a single reading. Indeed, most learners will not experience attrition equally across all skill areas.

"Intensity of Instruction." While length of time spent studying a language is related to ultimate achievement, the distribution of study over time is also important. Results of the Ottawa-Carleton French Project, for example, indicated that students enrolled for one year in a program, where half of each day's classes were conducted in French, made more progress than students exposed to the same number of hours' instruction spread over two years .Intensive programs of instruction have been reported to yield better results than less intensive programs of the same number of hours of instruction .These studies suggest that individuals intensively exposed to a language may use language acquisition processes different from those used by individuals involved in learning a language in chunks over long periods of time. Subsequent attrition rates may also differ for students of intensive and nonintensive programs of instruction.

"Developmental Considerations." Language learners of different ages and developmental levels bring different strengths and natural abilities to the language learning task. Children, for example, have a remarkable facility for rote memorization, and often retain intact memories in adulthood of material that has been untapped for years or decades. Adults, on the other hand, have metalinguistic and metacognitive skills superior to those of children. Their more advanced cognitive level allows them to rely on language consciously, to organize material in ways that will facilitate acquisition, and to recognize and plan for the possibility that skills may slowly deteriorate. The degree to which instructional methods capitalize on these developmental differences not only influences the learner's ease and success in acquisition, but may also affect the extent to which attrition is avoided.

"Curriculum Design." Foreign language instructors may incorporate maintenance techniques into the acquisition process by modifying the conventional linear syllabus to allow for the recycling of vocabulary and grammatical structures. Such design would permit review within the acquisition process, rather than requiring learners to refurbish their skills by plodding through the original material in exactly the same form as before. Research on specific design features that may prevent or slow down attrition is in its preliminary stages.

CULTURAL FACTORS

How do public attitudes toward bilingualism and the relative prestige of different languages influence the maintenance of second language skills? Insight may be gained from situations in which two or more languages come into contact. Such contact may occur for many different reasons, including, for example, changes in political boundaries, industrialization, emigration, and intermarriage. The result of language contact is usually a gradual shift in use from one language to the other. Factors related to language attrition or even the death of a language or dialect include the number and geographic concentration of speakers, age distribution of speakers, immigration patterns, and speaker literacy in the language involved. In instances in which one language is considered more prestigious than the other, it is unlikely that the less prestigious language would thrive across several generations. Chances of survival are even further reduced when negative attitudes toward bilingualism and strong societal pressures to assimilate are prevalent. Language shift from minority languages to English is particularly rapid in the United States, where the pressure for immigrant groups to assimilate linguistically has become so overt that several states have passed measures making English their "official state language." This kind of environment discourages bilingualism and hinders the study and maintenance of skills in languages other than English. In much the same way that a language restricted in domains of use becomes an impoverished and threatened language, an individual learner's language skills are prone to attrition in domains in which they are rarely used. For this reason, the presence of a strong ethnic community is important for the maintenance of foreign language skills. Foreign language learners can avail themselves of linguistic resources such as films, lectures, and newspapers in the foreign language. Large ethnic communities may also produce minority-language television broadcasts and sponsor live cultural events. These types of activities and resources provide valuable opportunities for foreign language learners to maintain their language skills.

PERSONAL FACTORS

A number of personality factors have been correlated positively with success in learning foreign languages. These include the willingness to take certain kinds of risks, good pattern recognition skills, tolerance for ambiguity in a number of situations, and an outgoing and social nature. A study found that non-English-speaking children who acquired English easily in an American school were those who sought out and became friendly with native speakers of English, taking advantage of every opportunity to socialize with these children and to practice their English skills . Moreover, learners of a foreign language are more successful if they understand the need to learn the language, and if they are motivated to do so . Indeed, the more positively the learner feels toward the language, the speakers, and the culture associated with the language being learned, the greater the progress that is made. There is a large body of research on the relationship among attitude, motivation, and language learning .The age of the learner acquiring the foreign language does make a difference because the chances of acquiring native-like speech appear to decrease over time. However, older students appear to learn morphology and syntax more quickly than young children. Students of all ages have an excellent chance of becoming proficient second language speakers if they are well-motivated, find the language interesting, and believe that the language is spoken by the kind of people they themselves would like to emulate.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE

Attrition is a powerful force, potentially causing even the most diligent and motivated learner or speaker to lose language skills that took years to acquire. Language study that helps the student to use the personal and cognitive strategies used by "expert learners" will enhance the likelihood of language skill maintenance; courses of study in which positive cultural attitudes are fostered and in which maintenance techniques are incorporated can help prevent attrition. Beyond these techniques, individuals can prevent attrition of their skills through travel abroad, the use of computer-aided instruction, self-instruction, and specific uses of cultural resources in their local ethnic communities. These techniques are described at length in You CAN Take It With You: Helping Students Maintain Foreign Language Skills Beyond the Classroom.